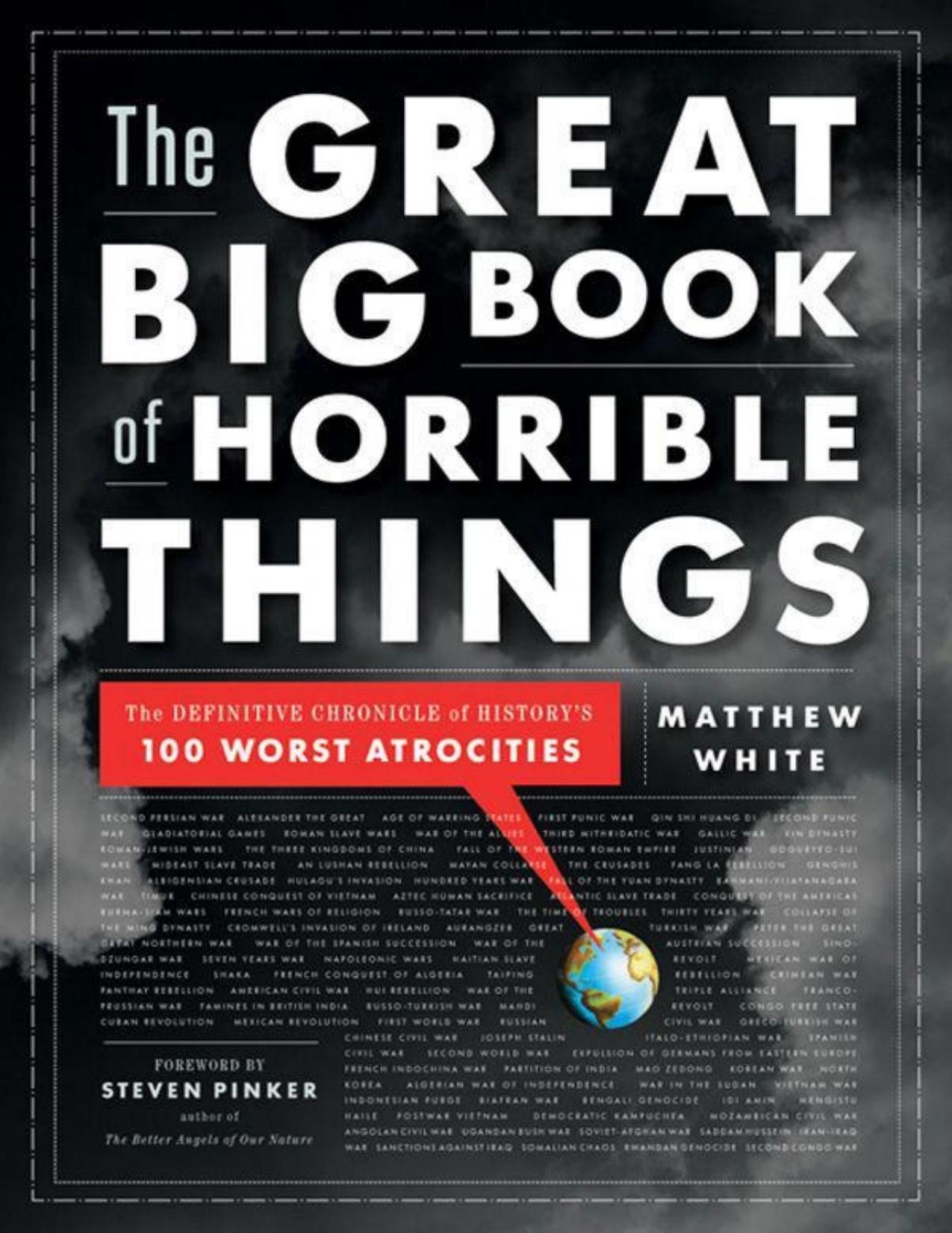

The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History's 100 Worst Atrocities by Matthew White

Author:Matthew White [White, Matthew]

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi, azw3, pdf

Tags: Religion, History, Non-Fiction, War, Politics, Reference

ISBN: 9780393081923

Amazon: 0393081923

Barnesnoble: 0393081923

Goodreads: 10955068

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Published: 2011-11-06T13:00:00+00:00

Taking a lesson from the gigantic national armies that had conquered Europe on behalf of Napoleon (see “Napoleonic Wars”) and France on behalf of Bismarck (see “Franco-Prussian War”), most regimes in Europe adopted universal conscription in the nineteenth century. The draft was popular with politicians on both sides of the aisle. The left wing approved of conscription because modern armies erased class distinctions and promoted by merit, putting arms into the hands of the people instead of the aristocracy. Reserve duty gave the nation an opportunity to provide a small measure of education, health care, and income to the working classes. The right wing liked national service because it promoted obedience, collected the masses to be washed and disciplined, and gave the government a tool to bully foreigners and dissidents. All across the continent, conscription created enormous armies that faced each other across disputed borders.3

Supplying, collecting, and deploying these giant national armies required railroads, and doing it right required carefully planned timetables. In case of war, reserve units would have to gather at the village train depot at the exact time to catch the exact train that was assigned to collect them. These trains would converge on the enemy’s border at fixed intervals to be unloaded quickly and then sent back for more troops—all without stalling or crashing into trains arriving from the wrong direction at the wrong time. In the event of a real war, speed mattered. Whoever got their armies mobilized and placed on the disputed border first could strike and penetrate many miles into essentially undefended territory for every day the enemy delayed.4

For years, contested borderlands had divided nations all over Europe. Germany and France squabbled over Alsace-Lorraine. Austria and Serbia both felt entitled to Bosnia; Italy and Austria quarreled over Tyrol, as did Bulgaria and Greece over Thrace, as did Germany and Denmark over Schleswig-Holstein. The ethnic boundaries of Europe were so convoluted that every nation had little alien enclaves that would prefer to belong to a neighboring country. It all sounds terribly complicated, but it created a very simple foreign policy: your neighbor was your enemy; your neighbor’s neighbor was your neighbor’s enemy and, therefore, your friend.

On the larger scale, nations also competed for mastery in the international pecking order. By beating France in 1871, Germany had become top dog of Europe, and the Germans had recently embarked on a massive shipbuilding program to challenge British dominance of the seas. Austria and Russia competed to replace the fading power of Turkey as lord of the Balkans. To pursue these rivalries each nation sought allies to back them up in a time of crisis. France, for example, needed someone on the other side of Germany to make the Germans think twice before invading again. The French could hook up with either Russia or Austria—it didn’t really matter—but whichever they picked, the other would attach itself to Germany by default. After a generation of shuffling, nudging, and posturing, Europe had divided into two power blocs—the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria, and Italy versus the Triple Entente of France, Britain, and Russia.

Download

The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History's 100 Worst Atrocities by Matthew White.mobi

The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History's 100 Worst Atrocities by Matthew White.azw3

The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History's 100 Worst Atrocities by Matthew White.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12022)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4922)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4784)

The Templars by Dan Jones(4686)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4489)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4209)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(4000)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3962)

Hitler in Los Angeles by Steven J. Ross(3943)

12 Strong by Doug Stanton(3544)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3334)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3201)

The Code Book by Simon Singh(3186)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(3124)

The Art of War Visualized by Jessica Hagy(3006)

Hitler's Flying Saucers: A Guide to German Flying Discs of the Second World War by Stevens Henry(2754)

Babylon's Ark by Lawrence Anthony(2674)

The Second World Wars by Victor Davis Hanson(2524)

Tobruk by Peter Fitzsimons(2514)